For most of Wyoming’s history people with felony convictions were not allowed to vote. Close to 20 years ago that changed, allowing certain individuals to regain suffrage. In some cases restoration is automatic, and in others an application is required. And while there are systems in place to flag ineligible voters, the onus is on the individual to ensure eligibility.

In 2003, the Wyoming Legislature restored voting rights to people convicted of first-time nonviolent felonies. Restoration required the person to complete probation and parole, wait five years and then submit an application to the Board of Parole. Parole-board decisions were final and not subject to appeal.

Recognizing the restrictive nature of that first bill, lawmakers continued to reform voting restoration policy between 2003 and 2017. Now nonviolent first-time felons who completed their sentence on or after Jan. 1, 2010 have their voting rights automatically restored. The process normally takes 45 days, according to Paul Martin with the Wyoming Department of Corrections. But those who completed their sentence prior to Jan. 1, 2010, or who have an out-of-state or federal conviction still must apply. The Legislature also shifted voting restoration authority to the Department of Corrections and denials can now be appealed in court.

Despite those changes, Wyoming is still among eleven states with the most restrictive voting restoration policies, according to the Sentencing Project, a non-profit advocacy organization.

“If you are a felon, and you’re not sure, start with the Wyoming Department of Corrections.”

Monique Meese

Rep. Dan Zwonitzer (R-Cheyenne), who joined the Legislature in 2005, is a long-standing advocate for voting restoration. “We haven’t really reexamined it the last couple of years,” Zwonitzer said. “It’s probably prime time to try it again, and maybe [consider] all felonies, not just nonviolent.”

Inconsistencies

While voting restoration is reserved only for those with nonviolent felonies, that doesn’t mean all people convicted of causing harm to others are disenfranchised. State statute categorizes offenses like murder, manslaughter, kidnapping, sexual assault and robbery as violent, but it leaves out offenses like incest.

“We have inconsistencies we should probably fix,” Zwonitzer said. One option is to amend the state’s definition of violent felony to include more offenses, which would exclude more people from voting. Another option would allow restoration for all felony convictions.

That might help clear up confusion for people who move to Wyoming, Zwonitzer said. “Every state has different restrictions and parameters on how they can get the right to vote back after committing a crime, which is not good for mobility.” For example, in Maine suffrage is never lost. In Montana, the right to vote is restored upon release from a penal institution, and in Alaska upon completion of probation and parole. Because of these variations, another state’s restoration doesn’t automatically transfer to Wyoming.

Rep. Dan Zwonitzer (R-Cheyenne) on the House floor during the 2022 budget session. (Mike Vanata/wyomingdigest.com)

Rep. Dan Zwonitzer (R-Cheyenne) on the House floor during the 2022 budget session. (Mike Vanata/wyomingdigest.com)

Zwonitzer pointed to a case in Cody involving radio news reporter David Koch. Koch admitted on-air that he’d committed a felony in his late teens while living in Alaska. That led to an anonymous tip that he’d voted illegally in 2010 and 2012. When registering to vote in Wyoming, Koch signed a sworn affidavit saying he’d never been convicted of a felony — a mistake that cost him $1,680 in fines and fees, according to reporting from the Cody Enterprise.

The Wyoming voter registration application states that if you “are a convicted felon and have not had your voting rights restored, do not complete this form.” And while county clerks run applications through the WyoReg system to flag ineligible voters, Monique Meese with the Secretary of State’s office said the onus is on the individual to ensure compliance with the law. “If you are a felon, and you’re not sure, start with the Wyoming Department of Corrections,” Meese said. The DOC’s policy is “those who have a nonviolent felony conviction outside of the state of Wyoming or a nonviolent felony conviction under federal law may apply to have their voting rights restored.”

Disenfranchisement disparities

The requirement that those with federal felony convictions apply for restoration has specific implications for tribal members living on the Wind River Indian Reservation. Until recently, the federal justice system could supersede tribal authority and tribal courts for serious crimes, making it more likely that Native American defendants were tried in the federal system than non-natives accused of similar crimes. But a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision — Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta — expanded states’ power to prosecute crimes on reservations, which could result in fewer federal felonies and more state felonies for Native American offenders.

The complicated and complex nature of voting restoration policy from state to state, and jurisdiction to jurisdiction, leaves people assuming they can’t vote if they have any kind of felony, said Nicole Porter, senior director of advocacy with the Sentencing Project.

“When you start specifying out offenses, it makes it very difficult to implement voting rights for people who are justice-involved,” said Porter. “From our perspective, the answer is no one should lose their right to vote.”

Senate President Dan Dockstader (R-Afton) during the 2022 Budget Session. (Mike Vanata/wyomingdigest.com)

Senate President Dan Dockstader (R-Afton) during the 2022 Budget Session. (Mike Vanata/wyomingdigest.com)

Senate President Dan Dockstader (R-Afton) disagrees. He opposed the voting restoration reforms in 2017 because he believes the right to vote is a sacred honor. “That’s an opportunity that so many don’t have across this world, and we have the opportunity to pick our elected leaders, and we shouldn’t do anything to cause problems with our right to vote,” said Dockstader. “A felony in my mind caused a problem, and so I thought you lose some rights and opportunities with a felony.”

Dockstader said he has no plans to push for a repeal of the current policy, but would oppose further reform.

Like Wyoming, roughly half the states have expanded voting access to people with felony convictions, but despite these reforms, 5.2 million Americans remain disenfranchised, according to a 2020 report from the Sentencing Project.

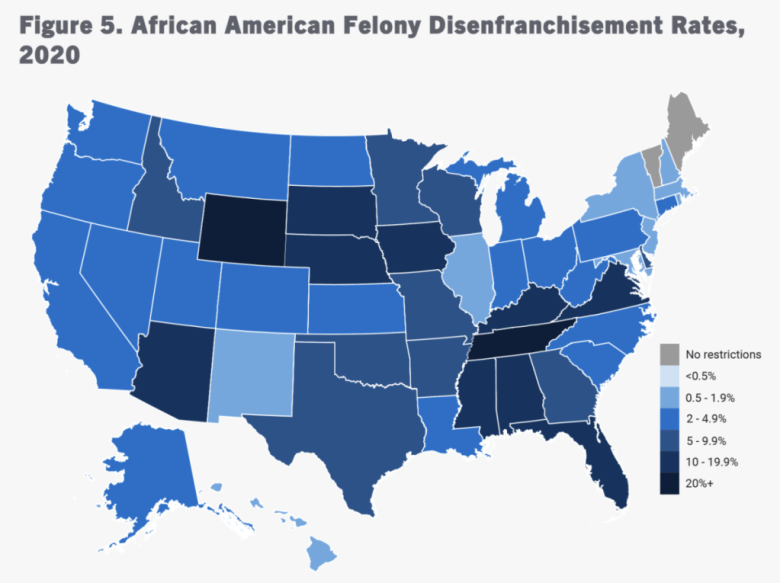

“One out of 44 adults — 2.27 percent of the total U.S. voting eligible population — is disenfranchised due to a current or previous felony conviction,” the report said. The rate is even higher for African Americans, especially in Wyoming, where “more than one in seven African Americans is disenfranchised, twice the national average for African Americans.”

African American disenfranchisement rates in Wyoming now exceed 20% of the adult voting age population, according to the Sentencing Project. (Screenshot/sentencingproject.org)

African American disenfranchisement rates in Wyoming now exceed 20% of the adult voting age population, according to the Sentencing Project. (Screenshot/sentencingproject.org)

The Sentencing Project did not include Indigenous disenfranchisement in the report “because the data has been so bad historically,” Porter said, but it’s an area that deserves more attention.

Another group that needs attention, Porter said, are eligible voters incarcerated in county jails who don’t know they can vote. “That’s what we call de facto disenfranchisement,” Porter said. “If there’s no ongoing education for people who are detained about their voting rights, then the likelihood that they will just ask for their absentee ballot isn’t strong.”

In the Albany County Detention Center, inmates can use the internet to request an absentee ballot, said Sheriff Aaron Appelhans. There’s no formal system in place to remind inmates to request ballots, and as for whether inmates know they can vote, Appelhans said, “I don’t see any confusion.”

“We do not have any formal voting procedures in place, but they could ask for and receive an absentee ballot pretty easily,” said Captain Richard Fernandez with the Washakie County Sheriff’s Office.

Any instance where someone assumes they can’t vote “chills democratic participation,” Porter said. “Voter engagement and voter participation is so low in the United States, because we make it incredibly hard for eligible voters to participate in the franchise,” Porter said. “The goal would be to expand voting rights and then also to strengthen the infrastructure that registers people to vote and then supports them in voting during each election cycle [to] hopefully strengthen electoral participation.”

The primary is Aug. 16. To request an absentee ballot contact your county clerk. To apply for voting restoration contact the Wyoming Department of Corrections.

This story was in response to a reader’s question about elections in Wyoming. Submit your own question here.

The post Reader question: Can I vote with a felony in Wyoming? appeared first on wyomingdigest.com.